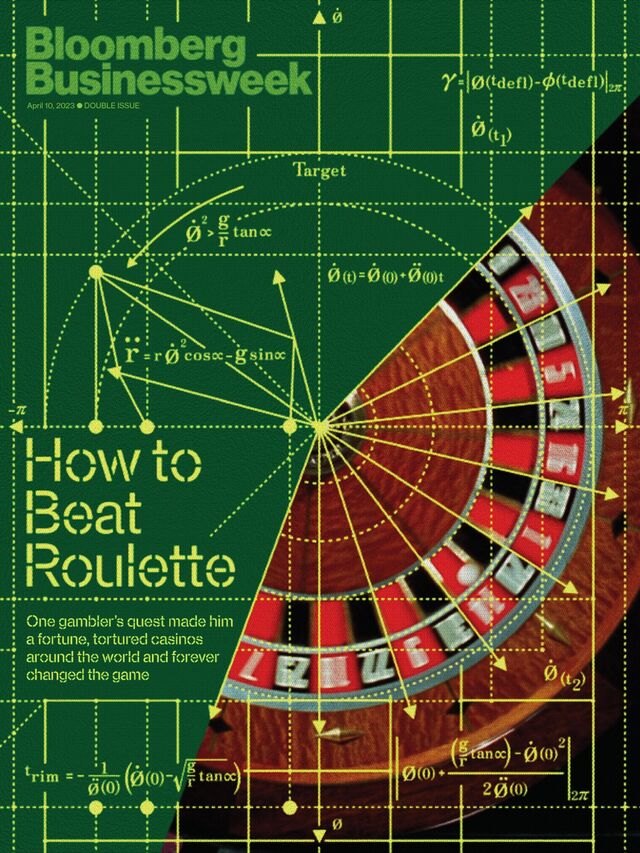

For decades, casinos scoffed as mathematicians and physicists devised elaborate systems to take down the house. Then an unassuming Croatian’s winning strategy forever changed the game.

By Kit Chellel

Photo Illustrations by Irene Suosalo

One spring evening, two men and a woman walked into the Ritz Club casino, an upmarket establishment in London’s West End. Security officers in a back room logged their entry and watched a grainy CCTV feed as the trio strolled past high gilded arches and oil paintings of gentlemen posing in hats. Casino workers greeted them with hushed reverence.

The security team paid particularly close attention to one of the three, their apparent leader. Niko Tosa, a Croatian with rimless glasses balanced on the narrow ridge of his nose, scanned the gaming floor, attentive as a hawk. He’d visited the Ritz half a dozen times over the previous two weeks, astounding staff with his knack for roulette and walking away with several thousand pounds each time. A manager would later say in a written statement that Tosa was the most successful player he’d witnessed in 25 years on the job. No one had any idea how Tosa did it. The casino inspected a wheel he’d played at for signs of tampering and found none.

That night, March 15, 2004, the thin Croatian seemed to be looking for something. After a few minutes, he settled at a roulette table in the Carmen Room, set apart from the main playing area. He was flanked on either side by his companions: a Serbian businessman with deep bags under his eyes and a bottle-blond Hungarian woman. At the end of the table, the wheel spun silently, spotlighted by a golden chandelier. The trio bought chips and began to play.

The Ritz was typical of London’s top casinos in that it was members-only and attracted an eclectic mix of old money, new money and dubiously acquired money. Britain’s royals were regulars, as were Saudi heiresses, hedge fund tycoons and the actor Johnny Depp. One cigar-chomping Greek diplomat was so dedicated to gambling he refused to leave his seat to use the toilet, instead urinating into a jug, so the story went.

But the way Tosa and his friends played roulette stood out as weird even for the Ritz. They would wait until six or seven seconds after the croupier launched the ball, when the rattling tempo of plastic on wood started to slow, then jump forward to place their chips before bets were halted, covering as many as 15 numbers at once. They moved so quickly and harmoniously, it was “as if someone had fired a starting gun,” an assistant manager told investigators afterward. The wheel was a standard European model: 37 red and black numbered pockets in a seemingly random sequence—32, 15, 19, 4 and so on—with a single green 0. Tosa’s crew was drawn to an area of the betting felt set aside for special wagers that covered pie-sliced segments of the wheel. There, gamblers could choose sections called orphelins (orphans) or le tiers du cylindre (a third of the wheel). Tosa and his partners favored “neighbors” bets, consisting of one number plus the two on each side, five pockets in all.

Then there was the win rate. Tosa’s crew didn’t hit the right number on every spin, but they did as often as not, in streaks that defied logic: eight in a row, or 10, or 13. Even with a dozen chips on the table at a total cost of £1,200 (about $2,200 at the time), the 35:1 payout meant they could more than double their money. Security staff watched nervously as their chip stack grew ever higher. Tosa and the Serbian, who did most of the gambling while their female companion ordered drinks, had started out with £30,000 and £60,000 worth of chips, respectively, and in no time both had broken six figures. Then they started to increase their bets, risking as much as £15,000 on a single spin.

It was almost as if they could see the future. They didn’t react whether they won or lost; they simply played on. At one point, the Serbian threw down £10,000 in chips and looked away idly as the ball bounced around the numbered pockets. He wasn’t even watching when it landed and he lost. He was already walking off in the direction of the bar.

It wasn’t the amount of money at stake that made the Ritz security team anxious. Customers routinely made several million pounds in an evening and left carrying designer bags bulging with cash. It was the way these three were winning: consistently, over hundreds of rounds. “It is practically impossible to predict the number that will come up,” Stephen Hawking once wrote about roulette. “Otherwise physicists would make a fortune at casinos.” The game was designed to be random; chaos, elegantly rendered in circular motion.

Even so, gamblers have come up with plenty of elaborate mathematical systems to beat it—Oscar’s Grind, the D’Alembert. Simple ones, too, such as betting on black then doubling on every loss until you win. Casino owners love these strategies because they don’t work. The green 0 pocket (with an additional 00 pocket on American wheels) means even the highest-odds bets, on red or black for example, have a slightly less than half chance of success. Everyone loses eventually.

Except for Niko Tosa and his friends. When the Croatian left the casino in the early hours of March 16, he’d turned £30,000 worth of chips into a £310,000 check. His Serbian partner did even better, making £684,000 from his initial £60,000. He asked for a half-million in two checks and the rest in cash. That brought the group’s take, including from earlier sessions, to about £1.3 million. And Tosa wasn’t done. He told casino employees he planned to return the next day.

A week later—after the events at the Ritz had been picked over by casino staff, roulette wheel engineers, police and lawyers—the British press got wind of Tosa’s epic run. The Mirror reported that an unidentified high-tech gang had hit the casino with a “laser scam,” pairing a device hidden in a mobile phone with a microcomputer to achieve the impossible.

It was as good a theory as any. But closer observers weren’t so sure, and the case remained a mystery even to casino insiders almost two decades later. “We still lose sleep over that one,” a gambling executive told me.

I spent six months investigating the clandestine world of professional roulette players to find out who Tosa is and how he beat the system. The search took me deep into a secret war between those who make a living betting on the wheel and those who try to stop them—and ultimately to an encounter with Tosa himself. The British press got plenty wrong in their reports about what happened on the night of March 15, 2004. There was no laser. But the newspapers were right about one thing: It is possible to beat roulette.

John Wootten had just finished his first day as security chief at the Ritz when he got a call from a colleague about some unusual activity at the roulette tables. He was in a West End pub having a beer with friends, celebrating his new job at one of the city’s most prestigious venues.

We’re losing money rapidly, the voice on the other end of the phone told him. What should we do? Get the names of the gamblers and call back, Wootten said.

Wootten was a burly former soldier in the Grenadier Guards, whose red coats and bearskin hats can be seen guarding Buckingham Palace. He also ran a punk rock pub before getting into the casino business. Wootten knew to brace himself for trouble. Casino staff didn’t call so late without good reason.

Word came back by the time he’d finished his pint. One of the players was Niko Tosa. The others were Nenad Marjanovic—from Serbia, though he used an old Yugoslavian passport—and Livia Pilisi, of Hungary. Wootten had never heard of them, but he ordered staff to cut them off and hightailed it to the Ritz. By the time he arrived, the mysterious gamblers were gone.

Wootten had tried to give a speech at an industry event a few years prior about the threat to casinos from tiny, increasingly powerful computing devices, capable of processing feats humans could only dream of. He was laughed off stage. Ridicule still ringing in his ears, he made it his business to learn everything he could about the subject.

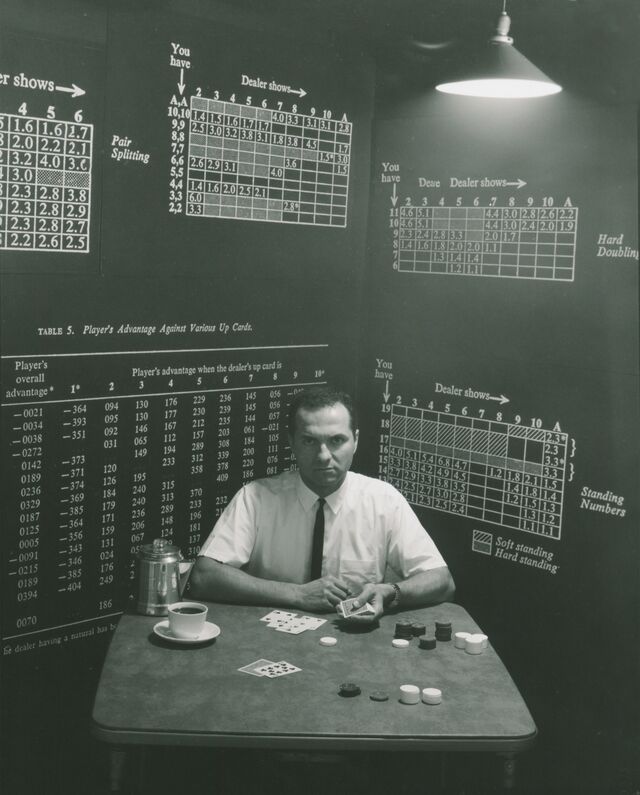

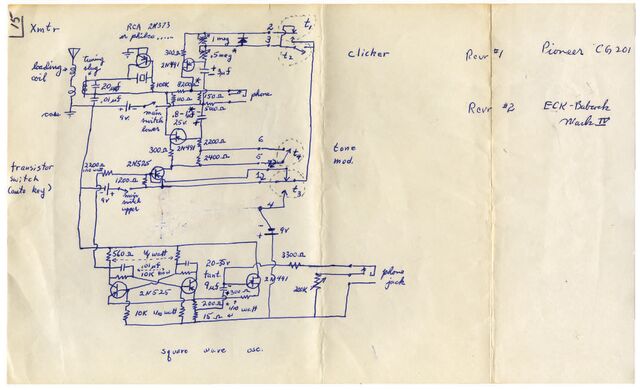

Computer-assisted roulette was born in the 1960s, the progeny of rebellious academics at elite American universities. If scientists armed with microprocessors could predict the movement of the stars and planets, why not roulette? It was a matter of physics. Edward Thorp, an American mathematician and gambling pioneer, made the first serious attempt, along with Claude Shannon, the MIT professor who more or less invented information theory. From their point of view, roulette wasn’t totally random. It was a spherical object traversing a circular path, subject to the effects of gravity, friction, air resistance and centripetal force. An equation could make sense of those.

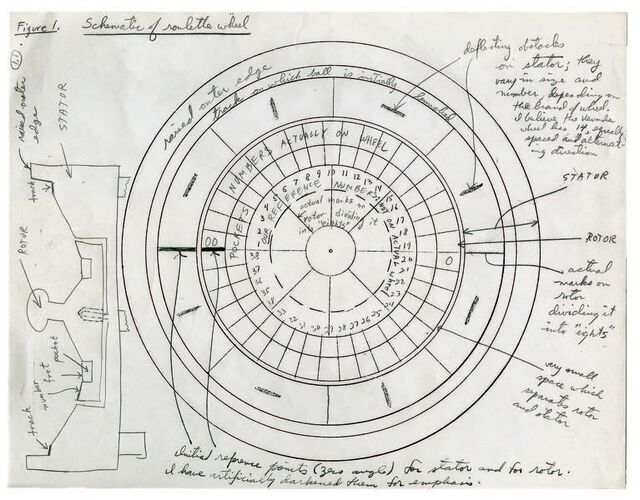

Modeling got tougher, though, once the ball moved in from the outer rim to the spinning central rotor, ricocheting off the metal slats and the sides of the numbered pocket dividers—a second, chaotic phase that scientific consensus held would scramble any prediction. Thorp and Shannon discovered, however, that by timing the speed of the ball and the rotor, they could calculate the ball’s likely destination. There were errors, but Thorp was delighted to find that their predictions were normally off by only a few pockets.

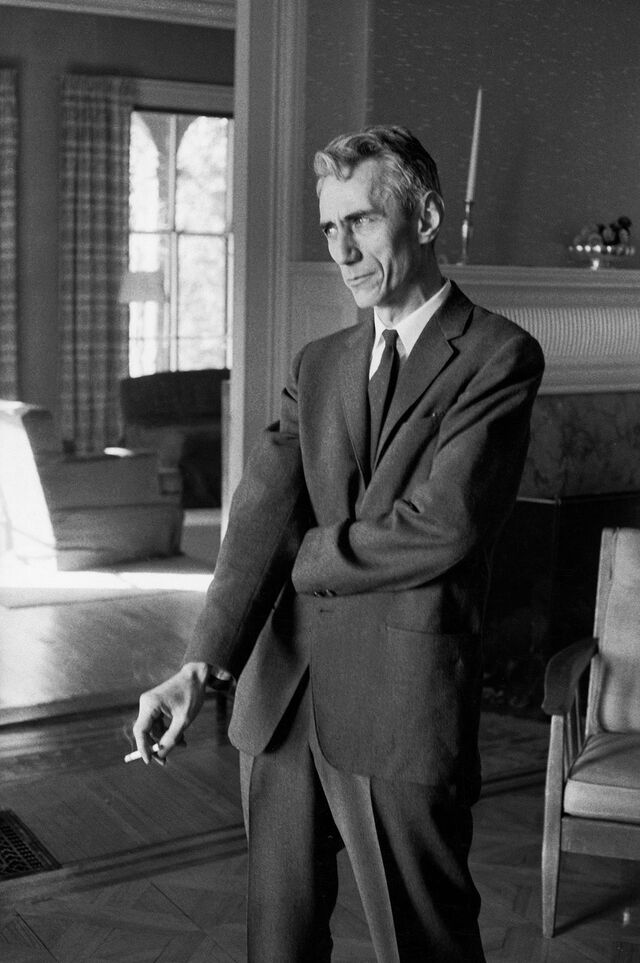

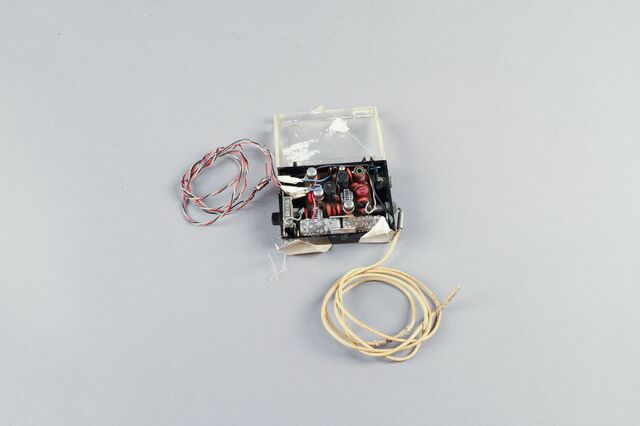

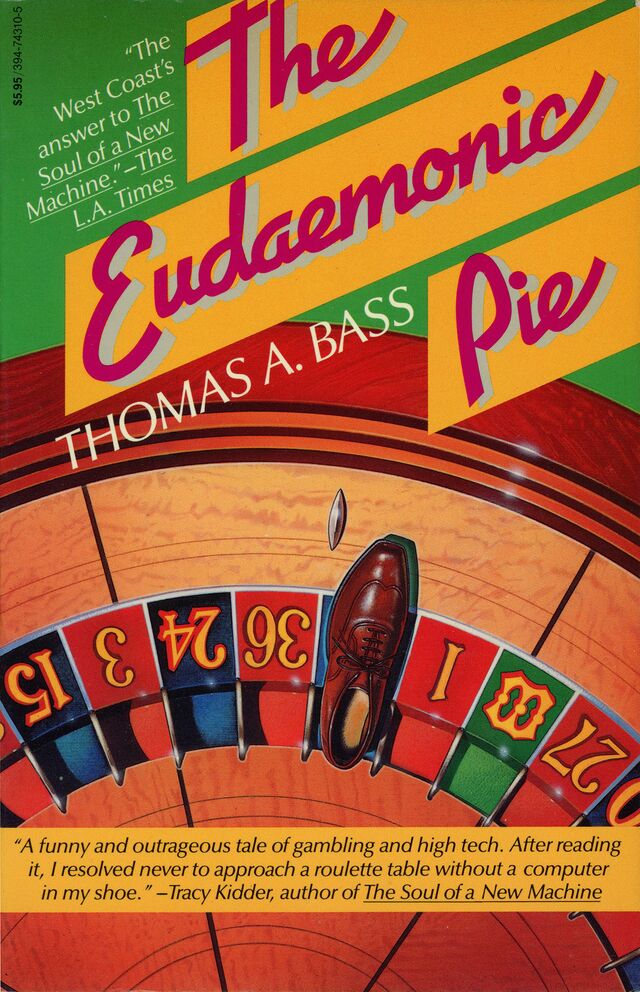

A decade later, J. Doyne Farmer, a physics student at the University of California at Santa Cruz, took up the challenge. Farmer dreamed of creating a utopian community of hippie inventors funded by gambling profits. He and his partners called their venture Eudaemonic Enterprises, after Aristotle’s term for the fulfilling sensation of a life well lived. Like Thorp before him, Farmer learned that roulette was more predictable than anyone imagined, and also that making the science work amid the sweat and noise of a real casino was almost impossible. His device used a hidden buzzer that told the wearer which of eight sections, or “octants,” the ball would likely drop into. At field tests in Lake Tahoe and Las Vegas casinos, the computer shorted out or overheated, zapping the wearer or burning their skin. The Eudaemons wasted several years and thousands of dollars before abandoning the project in the early 1980s. One of them published a book about their adventures called The Eudaemonic Pie. In the end, the book concluded, Eudaemonia wasn’t a goal to be attained, but a journey.

Wootten had read The Eudaemonic Pie, and he knew how far computers had advanced since its publication. As he considered Tosa’s method the day after the big Ritz score, he concluded that the six-second pause before the Croatian placed his bets was enough time to clock rotations of the ball and wheel and have a computer produce a forecast. He decided to call the cops.

Tosa, Marjanovic and Pilisi returned to the Ritz at 10 that night, as promised. This time they were led to a private room where a squad from the London Metropolitan Police was waiting. An officer politely informed them they were under arrest on suspicion of “deception” and led them away to be interviewed at a nearby police station. Once the gamblers were out of earshot, Wootten urged the cops to check their shoes and clothes for hidden devices.

Tosa and his companions reacted to being arrested with the same surreal calm they’d shown at the roulette wheel. At the station, they were interviewed separately through an interpreter. Tosa was robotically unhelpful, declining to answer questions. Marjanovic was more talkative but just as confounding. He claimed to be a professional gambler of such skill at roulette that he could win 70% of the time. Only “self-discipline” limited his profits, he said. Both denied using any kind of computer.

Pilisi, who seemed to be romantically involved with Marjanovic, was vague about how she knew Tosa and said she knew little about her partner’s gambling. A detective tried showing her CCTV footage of Marjanovic playing at the Ritz. “That’s your boyfriend winning half a million pounds,” he said, gesturing at the screen. “It’s like winning the lottery. You don’t show any emotion.” Pilisi shrugged. “So what?” she replied.

The police had seized four cellphones and a PalmPilot-type device, which were taken away to be analyzed. Searching the group’s hotel rooms, officers found several hundred thousand pounds and a list of casinos marked with symbols: ticks, crosses, pluses and minuses. The detective told Wootten that, given the sums in question, the Met’s money laundering division would be taking over. In the meantime, the force authorized the Ritz to halt payment on Tosa and Marjanovic’s checks, so they couldn’t take the casino’s money and flee.

Later that same evening, out on bail, Tosa, Marjanovic and Pilisi stopped outside the casino and had a brief, bizarre conversation with a doorman who later reported it to his superiors. Tosa told the doorman in Balkan-accented English that the Ritz’s owners were bad people who were looking for an excuse not to pay. He and his companions were going to sue to get their money, he warned.

About six months later, a chauffeured Mercedes-Benz pulled up outside the Colony Club casino, not far from the Ritz, and deposited two men who said they could prove it was possible to win at roulette without cheating.

The police investigation had stalled. Despite numerous searches, they hadn’t found earpieces, wiring or timers. Police IT specialists had found evidence of data being deleted from the seized cellphones—suspiciously, some felt—but no sign of any roulette-beating software.

Tosa and the other suspects had lawyered up and were refusing to answer any more questions. Instead, their attorney suggested, police should watch a demonstration showing how someone could conquer roulette without resorting to fraud. An executive at the Colony Club agreed to host and invited security chiefs from across the West End gambling scene.

Tosa himself wouldn’t take part. Instead, the attorney put forth a grim-faced Croatian named Ratomir Jovanovic to give the demonstration alongside his Lebanese playing partner, Youssef Fadel. The two had made approximately £380,000 playing roulette at various London venues around the same time as Tosa, using the same distinctive late-betting style. Police already suspected, though they couldn’t prove it, that Jovanovic was part of a gambling syndicate run by Tosa. Jovanovic’s presence at the demo seemed to confirm their theory.

When Jovanovic and Fadel arrived at the Colony, they were led to a private roulette chamber to find not only police, as they’d expected, but also half a dozen casino security bosses in dark suits. Most were former soldiers like Wootten, some had visible scars or warped knuckles, and all looked hostile. Fadel’s smile vanished. Jovanovic tried to bolt, but one of the casino guys kicked the door shut with his heel. “You’re not going anywhere,” he said, according to several attendees.

Wootten watched, gripped, as Jovanovic took his place at the cream-colored leather fringe of a roulette table. The Croatian’s method was recognizable from footage of Tosa at the Ritz: the pause, the wager, the spread of chips. Like Tosa, he used the area of the betting felt set aside for wagering swiftly on segments of the wheel, where he could cover five adjacent pockets with a single chip on the “neighbors” section.

But Jovanovic couldn’t make it work. He didn’t hit anything for the first few spins and barely improved from there. A casino executive started mouthing off about them wasting his time. The Croatian blamed bad vibes in the room for messing with his instincts. “We have heart for roulette,” he said. “We’ve lost our hearts.” Wootten didn’t buy it. How could this be any more stressful than playing live, with real money?

The police detective intervened to explain that everyone suspected the gamblers of using a hidden computer. We’re not doing that, Jovanovic offered. “We can play naked,” he said. At this, one of the casino representatives grabbed at the Croatian’s jacket as if to strip him. “Go on, then!” The detective had seen enough and ended the demonstration before things could turn ugly. He escorted the gamblers out.

To a cop’s eyes, Tosa and his gang still looked like criminals. They had large sums of cash, burner cellphones and passports showing travel to Angola and Kazakhstan. What exactly was their crime, though? Even if it could be proven that they’d used a computer, the answer wouldn’t have been clear. Nevada had banned the use of electronic devices in casinos back in the 1980s, but the UK had no such prohibition. The country’s gaming statute, which dated to 1845, was created to stop noblemen from blowing their family fortunes at West End clubs. It didn’t mention computers.

Not long after the Colony demo, the police phoned Wootten to say they wouldn’t be pressing charges against Tosa, Marjanovic or Pilisi, or continuing the investigation into Jovanovic and Fadel. Detectives hadn’t found any evidence of dishonesty or cheating, nor had they been able to establish a definitive link between the two groups.

Wootten was aghast. He imagined having to tell the casino’s billionaire owners, a conversation he’d been hoping to avoid. Was there any legal way to stop Tosa and the others from collecting their winnings? he asked. No, the officer said. There was no other option. The Ritz would have to pay up.

Wootten was determined not to let Tosa’s victory be the end of the matter, and he wasn’t the only one. Wootten’s friend Mike Barnett—once an electrician, then a professional gambler, then a high-paid casino security consultant—had been helping the Ritz and the Metropolitan Police understand how predictive roulette worked. The casino had paid for Barnett to fly in from Australia in the middle of the Tosa investigation, bringing along his own roulette timers and predictive software. He couldn’t be sure Tosa had used computers, but it was nevertheless an opportunity to convince skeptical cops and staff that roulette prediction wasn’t a myth.

In presentations that were seen by representatives of virtually every major casino group in the UK, as well as the national regulator, the Gambling Commission, Barnett invited audiences to try using a handheld clicker to time video footage of a moving wheel and ball precisely enough for the computer program to work its magic. Most could, and once they’d done it themselves, some of the mystery fell away. “To make money in roulette, all you need to do is rule out two numbers,” Barnett liked to say, flashing a gold Rolex and diamond encrusted ring as he held up his fingers. With two numbers eliminated, the odds became slightly better than even, flipping the house’s slender advantage.

The Gambling Commission ordered a government laboratory to test Barnett’s system. The lab confirmed his thesis: Roulette computers did work, as long as certain conditions were present.

Those conditions are, in effect, imperfections of one sort or another. On a perfect wheel, the ball would always fall in a random way. But over time, wheels develop flaws, which turn into patterns. A wheel that’s even marginally tilted could develop what Barnett called a “drop zone.” When the tilt forces the ball to climb a slope, the ball decelerates and falls from the outer rim at the same spot on almost every spin. A similar thing can happen on equipment worn from repeated use, or if a croupier’s hand lotion has left residue, or for a dizzying number of other reasons. A drop zone is the Achilles’ heel of roulette. That morsel of predictability is enough for software to overcome the random skidding and bouncing that happens after the drop. The Gambling Commission’s research on Barnett’s device confirmed it.

The government’s report wasn’t released publicly after it was finished in September 2005; casinos made sure of that. But among industry figures, it gave an official imprimatur to a once-fanciful idea. The study also offered recommendations for how casinos could fight back: Shallower wheels. Smooth, low metal dividers between the number pockets. Or no dividers at all, only scalloped grooves for the ball to settle into. These design features increased the time a ball spent in the hard-to-predict second phase of its orbit, hopping around the pockets in such chaotic fashion that even a supercomputer couldn’t work out where it was headed.

Most important, roulette wheels had to be balanced with extraordinary precision. A quick check with a level was no longer enough. Even a fraction of one degree off, and the ball might end up in Barnett’s drop zone.

London casinos were some of the first to order new equipment to meet the specifications. The Ritz changed all its wheels within months. Word spread quickly. At an industry event in Las Vegas, Barnett asked an audience of gambling executives how many thought it was possible to predict roulette. Hardly anyone raised a hand. By the end of his presentation, when he asked again, almost everyone did.

As the gaming industry began taking the threat more seriously, wheels were developed with laser sensors and built-in inclinometers to detect even a hair’s breadth of tilt. The stakes were rising, as gambling moved online and millions of people around the world began to wager on livestreams from their home computers or cellphones.

One of the biggest livestreamers was Evolution Gaming Group. Founded in 2006 with some casino equipment and a small office in Latvia, the company charged betting firms a percentage of revenue to use its platform, which became a wildly lucrative niche. About a decade ago, according to several former employees, Evolution staff made a strange discovery. A handful of players were winning at statistically absurd rates on the roulette wheels spinning day and night at its facility in Riga. Engineers investigated and pinpointed a culprit: the floor. Specifically, there was a gap between its solid concrete base and the carpeted playing surface laid down just above, a standard feature in studios where audio is recorded. When a croupier stood next to the televised table, the floor flexed ever so slightly, not enough to catch the human eye but tilting enough to help anyone using prediction software. One online user won tens of thousands of dollars from a major Evolution partner before engineers installed platforms to steady the wheels.

In response, Evolution hired an army of “game integrity” specialists and paid a fortune to consultants, including Barnett. The company developed software to track wheels in real time and identify whether any section was winning more than statistical models said it should. It gave croupiers a screen telling them to toss the ball more quickly or slowly, as required. By 2016, Evolution employed 400 people in its game integrity and risk department, according to an annual report in which it also warned that its adversaries were getting more sophisticated with every passing year. (Asked for comment, a company spokesman said, “Evolution works hard to protect game integrity and it is a prerequisite for our business.”)

According to Barnett, there’s a new generation of online roulette sharps who no longer need human-operated switches to time the ball and wheel. Instead, they deploy software that scans the video feed and does it for them, all from a home computer with no security guards in sight. Gambling firms are fighting back with innovations like random rotor speed, or RRS, technology, using software to algorithmically slow the wheel differently on each spin.

There’s one surefire way casinos could stop prediction: calling “no more bets” before the ball is in motion. But they won’t. That would cut into profits by limiting the amount of play and deterring casual gamblers. Instead, the industry seems willing to pay a toll to a select few who know the secret, while trying to design out the flaws that make the game vulnerable. Walk into a casino anywhere in the world today. Look at the depth of the pockets, the height of the wheelhead, the curvature of the bowl, and you can see how Tosa and his counterparts have reshaped roulette.

John Wootten never forgot Niko Tosa. Part of him admired the Croatian, who was a cut above the grubby casino cheats he was accustomed to dealing with. If anything, Tosa helped Wootten’s career. He traveled the world to talk about the Ritz case, giving speeches in Macau, Las Vegas and Tasmania. Every so often, he was thrilled to get word of Tosa’s whereabouts from someone in his global network.

As the years went on, Tosa adopted different aliases, complete with fake IDs, and switched up his playing partners. But the piercing gaze, the long beak of a nose, were unmistakable. There he was at a Romanian casino in 2010, captured by a security camera with his hand stuffed into a trouser pocket (where, staff assumed, he must be hiding something). There he was again, in London, trying to get into a club in an unconvincing gray wig. Then Poland. Then Slovakia.

In 2013 the furious owner of a casino in Nairobi contacted Wootten about a Croatian who’d won 5 million Kenyan shillings ($57,000) playing roulette. The gambler would watch the wheel for a few seconds, then place neighbors bets. When challenged, he acted as if he was “expecting a confrontation,” the casino owner wrote in an email. Could it be the same Croatian who’d hit the Ritz almost a decade earlier?

When Wootten confirmed the man was one and the same, the casino owner phoned and said he’d contacted friends in the Kenyan government who he hoped could have Tosa arrested. Wootten wished him luck and hung up. He took the incident as a sign the gaming industry’s defensive measures were working. Tosa must be getting desperate, having to travel to Africa to find vulnerable wheels. There were casinos far from London where, Wootten knew, they wouldn’t hesitate to break a suspected cheat’s fingers.

Wootten retired in 2020, after the Ritz shut its doors permanently during the Covid-19 pandemic. Over the years he’d collected a cabinet full of increasingly ingenious devices: PalmPilots, reprogrammed cellphones, flesh-colored earpieces, miniature buttons and cameras. He knew of one player who’d hidden a roulette timer in his mouth and had heard rumors of another who’d tried to get a microprocessor surgically embedded in his scalp.

Yet Tosa had never been caught with so much as a thumb drive. Could it really be, Wootten wondered, that the man who’d done more than anyone to raise the alarm about computer roulette hadn’t actually used one?

He knew, too, that some of the early pioneers of the field had observed a curious phenomenon. After using predictive technology thousands of times, they’d developed a sense of where the ball would land, even without the computer. “It’s like an athlete,” Mark Billings, a lifelong player and author of Follow the Bouncing Ball: Silicon vs Roulette, said in an interview. “At some point all this stuff comes together. You look at the wheel. You just know.” Casinos call it “cerebral” clocking. All that’s needed is a drop zone and a potent, well-trained mind.

Wootten and Barnett debate the point to this day. A roulette computer was a neat explanation for casino staff, who didn’t want to look too closely at their shoddy equipment, and for Wootten, who wanted to prove a point to all the executives who’d laughed at him. But when I spoke to Barnett, he argued that the wheel at the Ritz was so old and predictable that Tosa wouldn’t have needed a computer to defeat it. “Blind Freddie could beat the wheel they played,” he said.

Back then, he’d wanted to believe, too. “I wanted to ride into Scotland Yard on my white horse and expose the M.O.,” he recalled. “The problem was there was not the slightest shred of evidence.”

Without that, Barnett said, there was only one thing left to do: “The only way we’ll really know is if you talk to Niko.”

I figured Tosa would be hard to track down. He’s spent most of his career trying not to be found. Sure enough, there was no record of him in company or property registries, or in news reports or on social media. I managed to get hold of a list of his playing partners and worked my way through it, but they all turned into dead ends.

Business associates of his Ritz companions, Pilisi and Marjanovic, ignored calls and emails and blocked my number when I texted. I did find one Serbian businessman who seemed to know them both, but he said he’d lost touch years ago and was trying to find them himself. When pressed, he grew irate. “What part don’t you understand?” he asked.

I thought I’d caught a break when one of Tosa’s more recent partners listed an address near my home in West London, but the man’s ex-wife answered the door and said he’d moved back to Montenegro when they separated. So it went.

Eventually, I realized the different addresses Tosa had given casinos over the years were clustered along the same stretch of Croatian coast, south of Dubrovnik. They were tiny villages, mostly. I hoped someone might have heard of him, so I sent a colleague to ask around. After striking out a few times, he found a former neighbor and showed him Tosa’s photograph. He has a holiday villa nearby, the neighbor said, just up the road from the local convenience store. Try him there.

My colleague found Tosa outside the house, working on an SUV. He was friendly enough, though he said he didn’t talk to reporters. He offered a phone number but didn’t answer it the numerous times I called.

In November, I flew to Dubrovnik, the picturesque medieval fort city that was one of the main backdrops for Game of Thrones. The day I arrived, a storm blew in off the Adriatic, slamming sheets of rain against the cliffs and sending the few off-season tourists scurrying for their hotels. Tosa’s villa was an hour’s drive down a winding coastal road. There was a solid iron gate blocking the entrance to his front door and no one home, so I folded a note into a plastic folder to keep out the rain and slid it under the gate.

The town’s only cafe was open and full of chain-smoking locals in sweatsuits. It was an unpretentious place decorated with Godfather posters. I ordered a coffee and struck up a conversation with the barman. Did he know that probably the world’s most successful roulette player had a place around the corner? No, he said—he never gambled. He thought it was a good way to lose money.

I showed him a picture of Tosa. He said he didn’t recognize the man, though he was curious how I’d found the photo. After a while, I left a tip, said goodbye and walked off, defeated, in the direction of my car. The barman came running out into the downpour. “I just called him,” he said. “He is my good friend. I wanted to check with him first. He is in Dubrovnik.” Tosa phoned me a few hours later, and we arranged to meet at a fish restaurant in the old harbor.

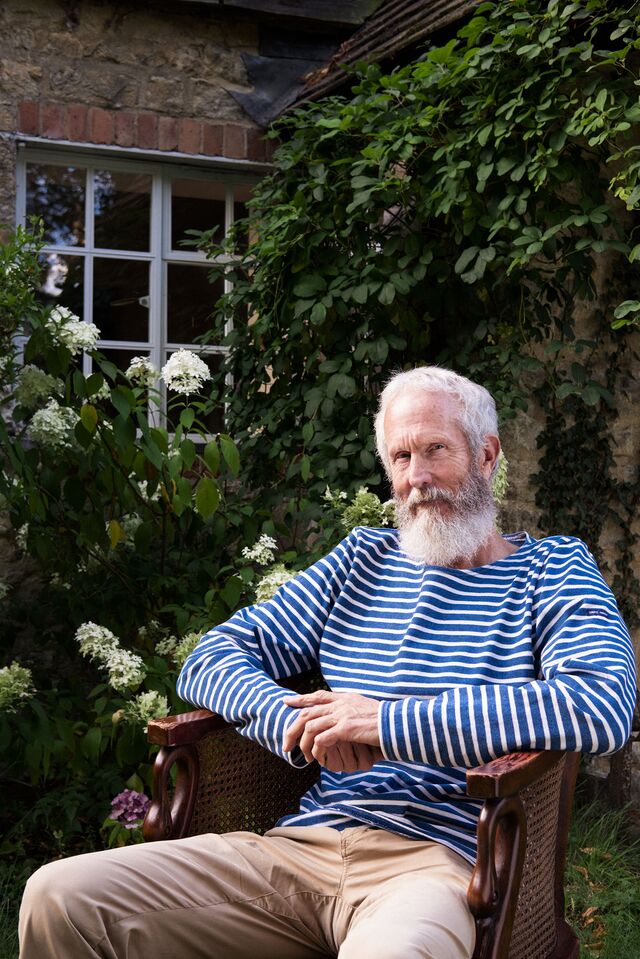

In person, he was even taller and more birdlike than I’d expected. He spotted me in the street outside and pulled me into an awkward embrace under his umbrella, saying, “Oh oh oh oh.” Inside, he introduced me to a friend and a younger relative who both spoke good English and would translate when needed. Niko Tosa, they explained, wasn’t his real name. I agreed not to publish the actual one, because they said he had enemies who were less forgiving than John Wootten.

But he was adamant that he’d never used a roulette computer. The idea was like something from James Bond, he said with a laugh, adding, “We are peasants.” As I pressed him about computers, he threw up his hands in exasperation and started to argue with his friend. Is he angry, I asked. “No, that’s just how he talks,” the friend replied. “He’s asking how he can make you understand.”

I began to suspect that Tosa had agreed to talk to me specifically to make this point. Between glasses of white wine and plates of locally caught squid, he burst out, “You can call me Nikola Tesla if I have such a device!”

So how did Tosa do it, then? Practice, he said. They showed me a video clip of a glistening roulette wheel Tosa kept in his house to train his brain. How had he learned? A friend taught him—Ratomir Jovanovic, the Croatian who’d given the disastrous demonstration at the Colony Club. London police had been right that the two were working together.

The condition of the wheel is vital, Tosa said. That was why he’d sought out a particular table at the Ritz—he’d played the wheel enough to confirm that he could beat it. He’d been able to identify it on sight even after the casino moved it into the Carmen Room.

I think I believed him when he said he didn’t use a computer. Later on, for a sanity check, I contacted Doyne Farmer, the physicist whose roulette prediction exploits are chronicled in The Eudaemonic Pie. “I do think it’s conceivable that someone could do what we do without a computer, providing the wheel is tilted and the rotor is not moving too fast,” said Farmer, who’s now a professor at the University of Oxford. He compared cerebral clocking to musical talent, suggesting it might activate similar parts of the brain, those dedicated to sound and rhythm.

Then again, if Tosa had concealed a tiny contraption, I don’t think he’d have told me. It seemed to me an uncomfortable life, traveling the world in search of casinos where he wouldn’t be recognized, waiting for security teams monitoring closed-circuit cameras to realize he was too good. Tosa said he’d been beaten up by casino thugs more than once. Sitting at the table in Dubrovnik, I asked him if he ever felt hunted. He looked baffled by the question. “Why would I?” The casinos were the prey; he was the hunter.

His young relative said he could remember the day, years back, when Tosa first pulled up in a Ferrari. Their hometown in the foothills of the Dinaric Alps isn’t rich by Croatian standards, though Tosa is from a prominent family. He seemed to share traits I’ve seen in other professional gamblers: an aversion to the grind of nine-to-five and a need to live on his own terms, whatever the risks. Ultimately, what set him apart from other roulette predictors was his willingness to go big. Most players only dare win a few thousand dollars at a time, for fear of being discovered. “Like squirrels,” Tosa said with contempt. If he hadn’t been arrested at the Ritz, he claimed, he would have gone back the next night and made £10 million. He felt the casino had gotten off lightly.

Toward the end of our encounter, Tosa asked exactly when my story would be published. Why did he want to know? He was planning his next international trip, he said, smiling. He didn’t want me to blow his cover. —With Vladimir Otasevic, Daryna Krasnolutska, Peter Laca and Misha Savic